Marcel Giró

Media

Palmira Puig: a camera of its own

Eva Vázquez. El Temps de les Arts

During the forced shutdown, the Fundació Vila Casas has moved the activity to its digital space, from where it offers virtual visits to the temporary exhibitions of its museums, with the corresponding online catalogues. Until the showrooms can be reopened, which has extended the programme until the summer, it is advisable not to miss the opportunity to get closer to the work of Palmira Puig (Tàrrega, 1912-Barcelona, 1978), a very interesting photographer who emerged unexpectedly in the midst of her husband's legacy, the also photographer Marcel Giró (Badalona, 1913-Mira-sol, Sant Cugat del Vallès, 2011), and who connects the photographic tradition of the Catalonia of the thirties with the modernity of the exuberant Brazil of the exile.

It is not every day that you discover an artist, and even less often that you end up finding her among the memories you already had at home. The chronicle of these unexpected dazzles is full of misplaced suitcases, drawers that closed badly, dusty garrets and abandoned boxes. But Toni Ricart arrived at Palmira Puig removing the very well ordered albums and negatives that his uncle, also a photographer, Marcel Giró, had left him, when he realised that many of the images bore her signature on the back, which she had been considered until then as an efficient but discreet collaborator of her husband in the advertising agency they ran in Sao Paulo. A first selection of this unpublished collection could be seen last year in the art gallery of Rocío Santa Cruz in Barcelona, and this spring it has arrived, enlarged with new findings, at the Palau Solterra of the Fundació Vila Casas in Torroella de Montgrí, where it will still be waiting for us, if the health control measures allow it, until the 21st of June.

It is an exciting exhibition from many points of view: for the privilege of enjoying a collection of images that has remained unpublished for more than fifty years, for the discovery of the Brazilian vein within the photographic avant-garde of the 20th century and for the seduction that this couple of advanced ideas and vital and hedonistic temperament exerts. The title itself contributes to the spell of double direction: the saudade, as Santa Cruz reminds us by quoting Lévi-Strauss, is not only the longing for the places where you have been happy, but also the feeling of loss that seizes you when you stumble upon the evidence that there is nothing permanent to hold on to. These "longings" for Sao Paulo, the land of exile that also ended up being the land of plenitude and prosperity, are a reflection of the harmony that this cultured and sporting couple from Republican Catalonia established with their host country, where they landed in 1948, just at the moment when Brazil was also immersed in the process of architectural, economic and cultural renovation that would make it the great laboratory of modernity in South America. But they are also nostalgic for having had to leave their land, which they remembered as dynamic and happy, and for not returning except to die, as in the case of Palmira Puig, of a fulminating cancer.

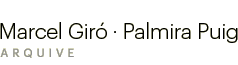

In their photographs, of a close communion with the visual formalisms of the Paulista school, one can perceive the hypnotic effect that the great metropolis under construction exerted, with vertiginous compositions of buildings, staircases and railings (a city that visually falls on you), but also the industrial signs, such as high tension lines or abandoned barrels, with which they sought the hard counterpoint, the strong contrast between light and shadow, and the dissolution of form in a play of geometric lines and undulations. It was that kind of look that had led to the Bauhaus experimentalism and Russian constructivism at the beginning of the century, and that had led to the field of the photographic image László Moholy-Nagy or Aleksander Rodtxenko before he crossed the Atlantic to also revolutionize the American vision. However, in Brazil, which was still entrenched in the Pictorialist aesthetics of the 19th century, these avant-garde discoveries arrived with a considerable delay, already in the 1950s, and with the help of neo-concretism, ready to be taken up by the Giró-Puig couple.

They did not arrive empty-handed: they were already coming from Catalonia with their eyes full. The little that has been documented so far of the couple's youth, before the war, reveals their interest in sport, political activism and also in photography, at the height of the amateur circuits that had been established since the 1920s by the country's photographic groups, which in fact channelled avant-garde concerns in connection with other international associations. Coming from a family dedicated to the textile industry, Marcel Giró was introduced to this visual research through the Agrupació Excursionista de Badalona, with which he participated in skiing championships, open water swimming races and all kinds of mountain expeditions, which on his return he divulged in some talks accompanied by photographic projections that already allow us to intuit the taste for foggy vertical angles that he would perfect years later among the imposing skyscrapers of Sao Paulo.

In Palmira Puig, who was also a tennis fan, her interest in photography surely came from her older brother, who shared a photo lab with that restless hiker from Badalona, from whom the girl would soon become inseparable. Daughter of a Republican congressman, she had grown up in a cultured and committed environment that would allow her to study mercantile expertise, promote the female group of Esquerra Republicana in Tàrrega and collaborate with the Catalan Government during the Republic and the war. More or less at the same time that Marcel Giró was joining the Pyrenean regiment as a volunteer, until in 1937, fed up with the squabbles between communists and anarchists, as his nephew explained, he deserted, like more than half of the detachment, to reach France by crossing the Pyrenees on foot.

The rest is a story all too familiar in the dramatic general uprising that followed at the end of the war. Palmira Puig watched as the Francoists requisitioned her house and threw her father's entire library out the window, while Marcel Giró, after taking refuge in France for a while, managed to get a ticket to Colombia, where he would use the family's wealth to set up a small textile business which, in the end, did not bear fruit. It was not until 1942, when they finally married by proxy, that the couple was reunited, and it was to start a new life in Brazil. In Palmira Puig's personal album, kept by her niece Ester Tayà, there are some photographs of that journey that was more of an adventure than a runaway, and many others of her period of adaptation to the new home that reflect a hopeful present. You can see them exultant, almost always outdoors, tanning in the sun, exploring lush landscapes or going into the slums to extract a note of life that contrasts with the brutal depersonalization of the mega city.

In a series of images in the album dated January 1949, shortly after their arrival in São Paulo, they are seen on a country outing with other friends, probably other expatriates, during which they end up dancing a sardana. Their adaptation to the host country was never a withdrawal from their origins. Proof of this are the frequent trips to Barcelona and a stay in Ibiza around 1955, from which they returned with images of rustic whiteness that had been confused by some remote Mexican village until the journalist Antoni Ribas Tur recognised the church of his hometown. No less significant is the appreciation they professed for the painter Francesc Domingo, also established in Sao Paulo, with whom they would travel around 1960 to the fabulous spot of Vale da Lua, in the Alto Paraiso of Goiás, where Marcel Giró would portray him trapped, like a docile grasshopper, on a lunar rocky outcrop. Toni Ricart explains that Giró would take advantage of this same rocky fantasy to design the advertisement for a brand of electrical appliances for the advertising agency that he had opened in 1953 with his wife and from which one of Marcel's most emblematic images would come out: that of the Afro-Brazilian girl holding a dove, conceived as a Christmas card.

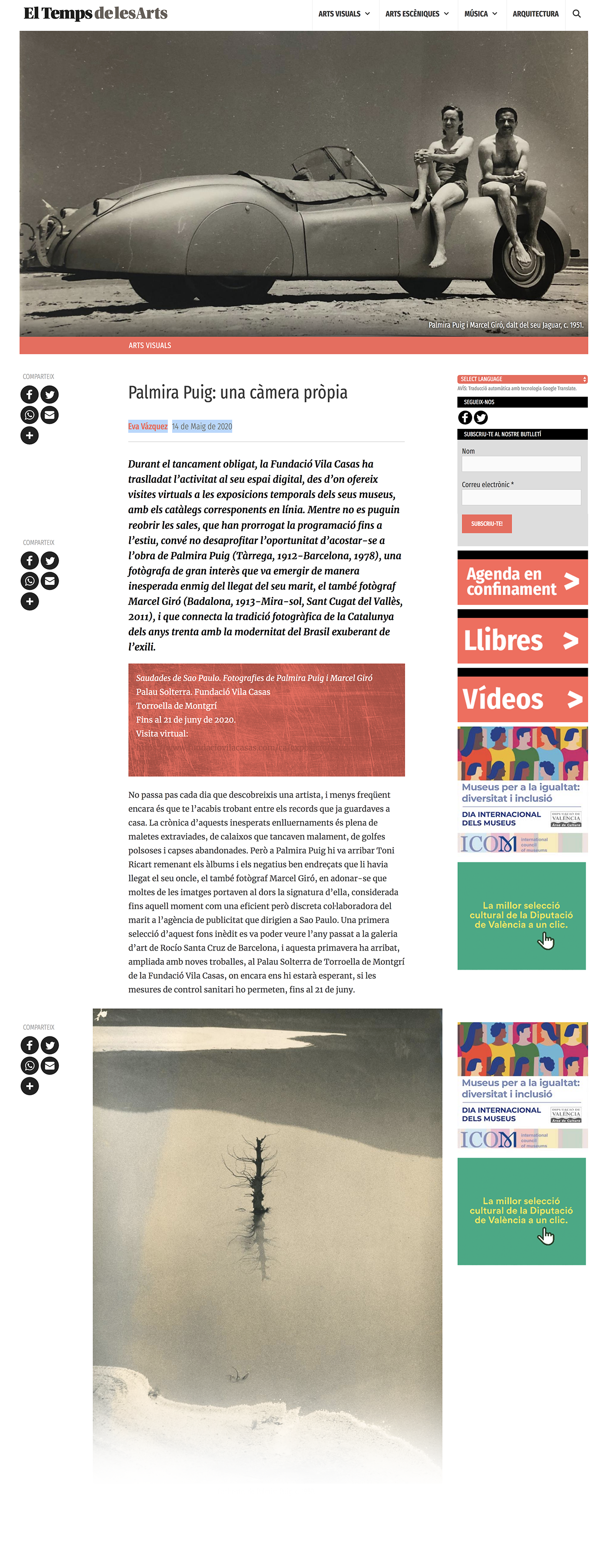

All that is charming about this Catalan couple is also the obstacle. The complicity that united them from their first youth, and which is reflected in the portraits they would take of each other and in the happy way they reinvented themselves in the new world (the photograph of the two in swimsuits on top of the Jaguar is impressive), may lead one to believe that in the creative field they also formed a type of indivisible society that the fact of having located contact sheets signed or intervened by both of them has just confirmed. The hypothesis is comforting and, as far as their shared life is concerned, it is certainly true, but for the researchers it represents a very common drawback: to delimit well what corresponds to each one. Even the camera, they insist, was shared, even though in the portraits it is clear that each one was carrying his own. Toni Ricart has done a great job in making this unpublished family collection known, but it is undeniable that the main effort has been reserved for Marcel Giró as a preeminent member of the Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante, the entity that brought together the pioneers of the photographic avant-garde in Brazil and of which he was a member since 1950, as well as she, from 1956. Throughout the operation to rescue the work of the Giró family, there has been an implicit conviction that he is the truly relevant figure, and that Palmira Puig, to whom little work has yet been attributed, was a kind of luminous coincidence.

It is true that Marcel Giró's love of photography can be documented as far back as the 1930s, under the guise of hiking, while Palmira Puig has no record of any training prior to her arrival in Brazil and her husband's entry into the Bandeirante club. But it should not be forgotten that this organisation, in line with the discriminatory mentality of the time, gave very little public space to women, none of whom were awarded prizes in the salons or, of course, were ever on the selection and qualification panels. Examining the photoclub bulletins of those years, however, it is discovered that Palmira Puig was one of the women who participated most often in the national and international exhibitions of the entity, together with Gertrudes Altschul, Barbara Mors, Dulce G. Carneiro, Menha S. Polacov, Maria Helena S. Valente da Cruz and Alice A. Kanji. They were few, very few, compared to the number and prestige that their male colleagues, who were often their husbands, would achieve. But there is no doubt about the courage and sensitivity with which they also embraced modernity and assimilated the legacy of the interwar avant-garde that the important Central European exile colony had brought to America.

The Palau Solterra has perhaps lacked the audacity to let the work of Palmira Puig stand on its own, without the somewhat overwhelming accompaniment of that of Marcel Giró, which has already been appreciated in other exhibitions organised, since its rediscovery in 2016, by the same Rocío Santa Cruz gallery. In any case, the scarcity of photographs that can be attributed with complete certainty to Palmira should be an incentive to continue researching the nearly 4,000 negatives and hundreds of contact sheets in the Giró archive in order to restore his authorship rights. This is the challenge.

It is not every day that you discover an artist, and even less often that you end up finding her among the memories you already had at home. The chronicle of these unexpected dazzles is full of misplaced suitcases, drawers that closed badly, dusty garrets and abandoned boxes. But Toni Ricart arrived at Palmira Puig removing the very well ordered albums and negatives that his uncle, also a photographer, Marcel Giró, had left him, when he realised that many of the images bore her signature on the back, which she had been considered until then as an efficient but discreet collaborator of her husband in the advertising agency they ran in Sao Paulo. A first selection of this unpublished collection could be seen last year in the art gallery of Rocío Santa Cruz in Barcelona, and this spring it has arrived, enlarged with new findings, at the Palau Solterra of the Fundació Vila Casas in Torroella de Montgrí, where it will still be waiting for us, if the health control measures allow it, until the 21st of June.

It is an exciting exhibition from many points of view: for the privilege of enjoying a collection of images that has remained unpublished for more than fifty years, for the discovery of the Brazilian vein within the photographic avant-garde of the 20th century and for the seduction that this couple of advanced ideas and vital and hedonistic temperament exerts. The title itself contributes to the spell of double direction: the saudade, as Santa Cruz reminds us by quoting Lévi-Strauss, is not only the longing for the places where you have been happy, but also the feeling of loss that seizes you when you stumble upon the evidence that there is nothing permanent to hold on to. These "longings" for Sao Paulo, the land of exile that also ended up being the land of plenitude and prosperity, are a reflection of the harmony that this cultured and sporting couple from Republican Catalonia established with their host country, where they landed in 1948, just at the moment when Brazil was also immersed in the process of architectural, economic and cultural renovation that would make it the great laboratory of modernity in South America. But they are also nostalgic for having had to leave their land, which they remembered as dynamic and happy, and for not returning except to die, as in the case of Palmira Puig, of a fulminating cancer.

In their photographs, of a close communion with the visual formalisms of the Paulista school, one can perceive the hypnotic effect that the great metropolis under construction exerted, with vertiginous compositions of buildings, staircases and railings (a city that visually falls on you), but also the industrial signs, such as high tension lines or abandoned barrels, with which they sought the hard counterpoint, the strong contrast between light and shadow, and the dissolution of form in a play of geometric lines and undulations. It was that kind of look that had led to the Bauhaus experimentalism and Russian constructivism at the beginning of the century, and that had led to the field of the photographic image László Moholy-Nagy or Aleksander Rodtxenko before he crossed the Atlantic to also revolutionize the American vision. However, in Brazil, which was still entrenched in the Pictorialist aesthetics of the 19th century, these avant-garde discoveries arrived with a considerable delay, already in the 1950s, and with the help of neo-concretism, ready to be taken up by the Giró-Puig couple.