Marcel Giró

Imprensa

Vênus e Adonis, por Estudio Giró

Josep Casamartina, Mirador de les Arts.

One of the most famous paintings by Titian is Venus and Adonis, and it enjoyed so much success at the time that many replicas were made of it, with minimal variations. In the work, the artist does not focus on the myth portrayed by Ovid, but is a free version and one which, to this day, we cannot be sure whether it is of his own invention.

It encapsulates opposing standards of behaviour, male and female, which have impregnated most societies for centuries and centuries.

Titian’s Adonis is a stocky young man, in the strictest sense of the word, with a round face framed by chestnut-coloured curls. His clothes only half cover his chest and he is walking decisively forward, pulled by three large hunting dogs. Venus, completely naked, is crowned by golden plaits. She is with her back to the viewer, leaning back with her right arm across the torso of the boy, clinging on to stop him from leaving. They are looking at each other intently, but he is moving forward, almost dragging her with him because she will not let go, and the dogs are pulling hard. We do not know if they have just made love…but we should probably assume they have because the of the presence of the little Cupid or Eros, who is lying asleep in the branches on the left of the background. In Ovid’s story, she foresees, in vain, the danger that will lead him ominously to his death if he goes hunting. Another interpretation of the scene, although one which is not now the case, is that Adonis is gay and not sexually interested in ladies.

But beyond the beauty of the work, Adonis, the man, represents movement, decision, moving forward, and Venus, the woman, represents calm and sensuality. He is moving on and is unstoppable while she is relegated to make him stay by offering pleasure at the table and in bed. The Bible, the origin of all inequalities of gender and the most pronounced of all sexism begins by establishing the abyss between the two sexes right from the start, ennobling the male and denigrating the female. Eve is not the rib of Adam because all you will find on a rib is a chunk of meat and fat, and there are no metaphors for that.

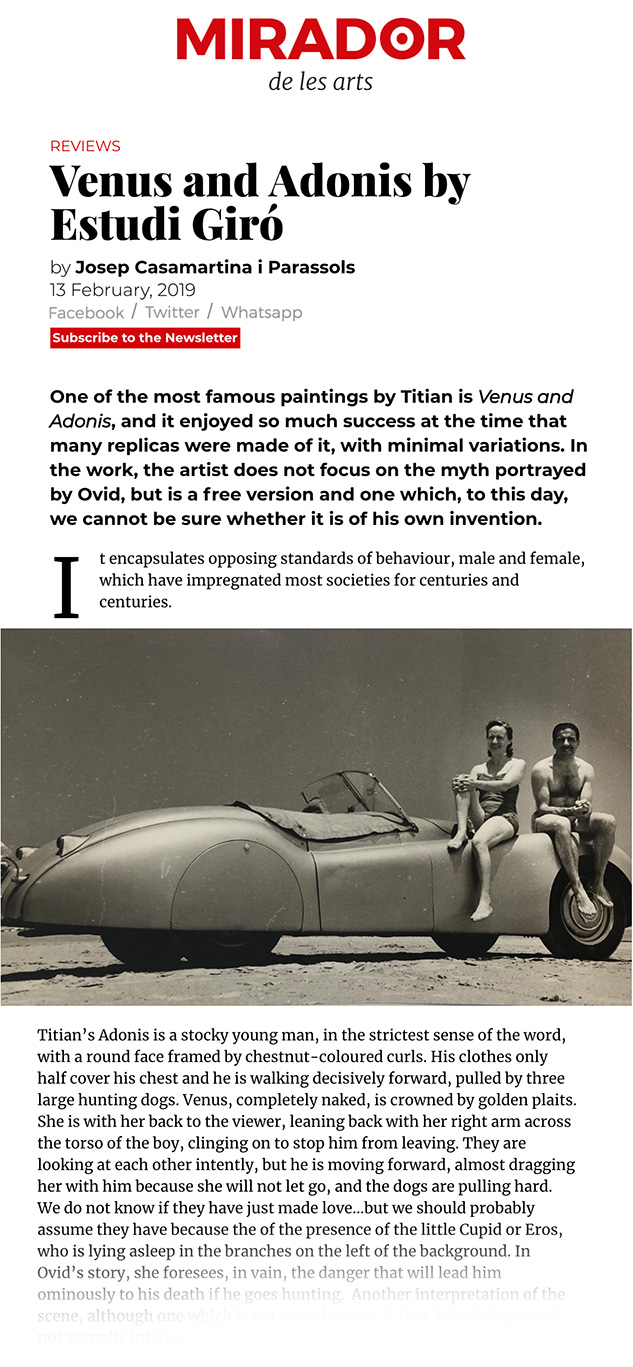

Almost five hundred years after Titian, the Venus and Adonis appears again, , in a double self-portrait, this time by the Estudi Giró, on the outskirts of São Paulo. The year is around 1950 and everything seems to have radically, at least as far as those two are concerned. They are wearing bathing suits. Adonis is still stocky, from working out at the gym, Physical Culture style, and Venus is sitting beside him with one leg tucked under and she is not tugging at him. Nobody is holding anyone back. The three hunting dogs have become a shiny, new Jaguar convertible –an XK 120 Roadster model, parked on the beach. There is no hint of tension and judging by the type of car they are sitting in, and also their relaxed appearance it would seem that things are going very well for them. Eros/Cupid doesn’t get a look in because this couple don’t need any incentives.

Marcel Giró, the Adonis in the photo, fled Catalonia at the end of the Civil War and went to Columbia. Palmira Puig, the Venus of the Jag, was also from a Republican family, and went to find him as soon as she was able to leave Spain, after entering into a marriage of convenience in 1943. From Columbia they moved to Brazil. Giró, who was from Badalona, tried his luck in the textile industry but it didn’t work out. Palmira set up a photographic studio for advertising and marketing, with which she did really well, and it would soon become one of the biggest in the country. That must be where the Jaguar came from! Two years ago, the RocioSantaCruz gallery presented a magnificent exhibition of the work of Marcel Giró which was a total revelation. In fact, since 2011 Giró’s work has gone from strength to strength, first in South America in the context of the review of the so-called Paulist School, which was a pioneer in introducing modernity to Brazil in the field of photography.

As one studies and goes deeper into Giró’s work, a surprise appears, in that Palmira was actually the author of many of the works that until now everyone thought were by him, because when they went out to take photographs, they used the same camera, passing it from one to the other with complete naturalness. It doesn’t seem as if either Marcel or Palmira nursed any desire to be famous through their creations. They exhibited every once in a while, in group exhibition at the Cine Club Bandeirante, of which they were both members, and carried on working. Nor does it seem that there was any competitiveness or relation of superiority between them. The worked together and took forward together creative work which was also a business and one which worked very well for them. If in 2017 the RocioSantCruz gallery offered us a better understanding of the impeccable and exquisite photographic production of Marcel, now it brings us Palmira, who has so much in common with him. And it is a fantastic idea that one day we might just be able to call them Estudi Giró because one day we may not need to distinguish them.

The exhibition Palmira Puig-Giró, photographer can be seen at the RocioSantaCruz gallery in Barcelona, until 16 March 2019.